No Clearer

It has been exceedingly fortunate that 2019 began on January 1st. The performance of financial markets this year has been deceptively flattered by the plunge in equities towards the end of last year, the nadir of which broadly coincided with the turn of the year. To argue that 2019 has been a good year for investments would beg an accusation of disingenuity. It is more helpful to look back over the whole of the previous twelve months and to say that markets have progressed a little. But generally not a lot.

There. That was a whole opening paragraph without a single mention of Brexit, Boris, Trump or the trade wars. We are now going downhill rapidly. I apologize, but we shall need to come back to these before we are done.

For financial markets, the stand out feature of the year so far has been a dramatic fall in bond yields. This has accompanied a significant reassessment of the outlook for global economic growth, and not in a good way. Earlier fears of wage-driven higher inflation have been replaced by a conviction that the ‘trade wars’ in particular will instead have a meaningful negative effect across the world: lower growth and less inflation.

The stand out feature of the year has been a dramatic fall in bond yields

The yield (the rate at which one receives income or interest) on the 10 year US Treasury Bill has fallen from over 3% last autumn to, temporarily, less than 2%. The yield on the UK 10 year gilt has halved over the same period; at the time of typing this, you had the opportunity to lend money to the UK government (Boris, or Jeremy, or whoever) for the next ten years at the astonishingly low rate of 0.8% per annum.

It is a stretch of the imagination to say that this looks an irresistible investment opportunity. That, however, is a potentially dangerous simplification of the situation. The deal would also have looked just as terrible last autumn, when you could have received (what appeared) a paltry 1.6% per annum. The mathematics of bonds means that the price of the 10 year gilt (standing in the dock, accused of being expensive) has risen by 7% in the past nine months. If we include the interest payments and annualize the returns, it is the equivalent of a gain of around 10%. That is a pretty decent outcome from what might have appeared a terrible starting point.

Yields on bonds have been falling, on and off, since 1980. Over the past decade alone the yield on the 10 year gilt has halved twice, and then fallen by a further 20%. Can it possibly halve again? It would be brave to rule it out (ignoring that we do know that something can halve an infinite number of times). The argument in favour of this happening would be that we are in a period of lower economic growth and technology-driven disinflation, augmented by the disruptions of Trump’s trade policies, et al. It is a line of thinking with which we admit a degree of sympathy.

Our portfolios typically hold a good proportion of bonds, a strategy sometimes unpopular with those believing that higher inflation is about to come knocking on our doors. These bonds have tended to serve us well and we are not at the point of thinking that we need to change our conviction in their merits.

President Trump, of course, could start a fight in a game of solitaire. His is a complex personality, but with a consistency, whereby he will battle anyone or anything that he thinks is not in the best interest of the United States. Love him, loathe him, ignore him; whatever one’s point of view, he and his entourage are unsettling global trade in a way that is, in the short-term, rather harmful. Global manufacturing, as measured by the Purchasing Managers Index, is the weakest it has been since 2012.

We do not profess to know what will happen next. Mr Trump is standing for re-election next year and doubtless would wish to deliver a trade deal or two in the meantime. It is to everyone’s benefit that these should happen and logic suggests that a degree of sanity will return over the next twelve months. That though is a hope rather than an expectation.

Logic suggests that a degree of sanity will return

Equity investors have not taken fright, thus far. To the contrary, they have been heartened by the developments: higher interest rates are now less of a threat, instead there is a dangling carrot of lower rates. Our portfolios have benefited from this unexpected, but welcome, tailwind. We suspect, though, that this is a gust rather than a change in the prevailing wind direction. Lower interest rates need to be justified by lower economic growth, which in turn means current expectations for company profits will be, on average, too high.

The UK equity market has not had a bad year so far, but is lagging the majority of the rest of the world. The rationale is simple enough: the prospects of either a No Deal Brexit or a Corbyn-led Labour government are more than enough to scare both domestic and international investors. And us. Having started this year with the belief that UK domestic assets were over-sold and under-priced, we saw an encouraging number of very sharp share price recoveries. We are now in the position whereby these domestic shares are priced considerably higher than six months ago, but also where the risks of No Deal or Corbyn have risen dramatically. The scales of safety have tilted away from us.

It is inconvenient that the timing of Boris’s confirmation as Prime Minister is likely to fall between our writing of this and its dropping onto your doormat. The range of possibilities of what might now happen over the remainder of the year is bewildering and makes the appropriate planning of portfolios even more of a challenge. We are inherently cautious investors and uncertainty as acute as this will always push us to seek to protect the real value of the assets that we manage, rather than to try to guess where the biggest gains may be. The inclination of a tortoise to go into its shell from time to time does not preclude it from beating the hare over the long run.

Thus we go into the third quarter of the year with almost exactly the same threats and opportunities as the previous one. And the one before that. Yet again, we hope that by the time we write the next edition of Underneath the Arches, the course of events will have become clearer. For some reason, we doubt it.

Jim Wood-Smith – Chief Investment Officer, Private Clients

Jim Wood-Smith – Chief Investment Officer, Private Clients

Net Zero

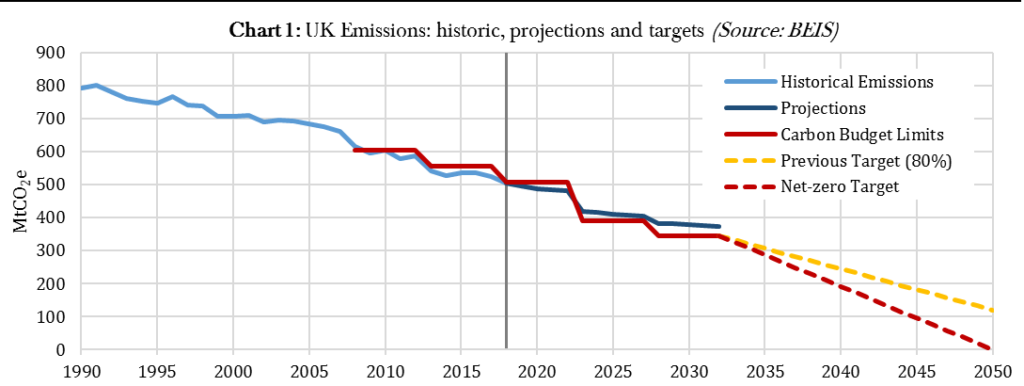

In April 2019, the statutory body that advises the government on preparing for climate change declared that the UK should target net-zero carbon emissions by 2050. For some, the Committee on Climate Change’s (CCC) recommendation is outrageously ambitious; even the prior 2050 target of an 80% reduction in emissions relative to 1990 seemed a Herculean challenge (Chart 1). For others – most vociferously the Extinction Rebellion protesters – a 2050 net-zero target is not nearly urgent enough and must come decades earlier.

Our emission targets form from a patchwork of the 1997 Kyoto Protocol, the 2008 Climate Change Act and, most recently, the 2015 Paris Climate Agreement. Though to date these budgets have been met or exceeded, the UK is currently not on track to meet the 2023-2027 target. Meanwhile, a 2050 net-zero target would require even greater changes to policy and our daily lives (Chart 1).

The added nuance to the CCC’s recommendation is its renewed call to include aviation and shipping in the emission target. Critics, such as Greta Thunberg, accuse the UK Government of “very creative carbon accounting” by narrowly reporting progress on only territorial emissions: it is all too easy to shift responsibility overseas. Climate change is after all a global, not a territorial, problem. Were the CCC’s revised definition adopted, that net-zero target is all the more difficult to achieve. Either way, the extent of change required for the UK to stay in budget is huge.

If the meticulous and robust expert advice here is heeded it will deliver a revolution in every facet of our lives, from how we power our homes and travel to work to the food we buy.

Prof David Reay, University of Edinburgh, May 2019

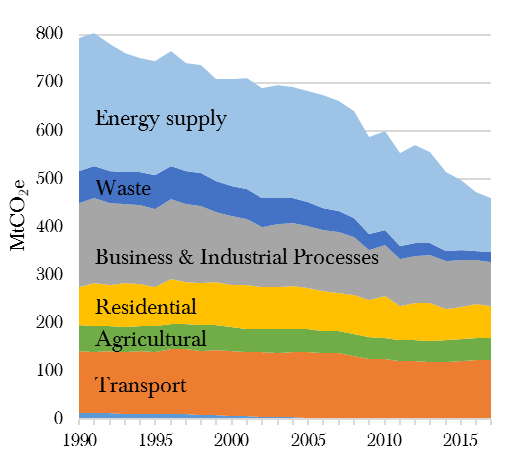

Chart 2: UK emissions by sector, 1990 – 2017

(Source: BEIS)

Beneath the surface, the energy sector has done much of the UK’s emission-reduction heavy lifting to date (Chart 2 above). Specifically, the reduced use of coal for electricity generation has meant a 60% decrease in energy supply emissions. Other sectors have been less amenable: transport emissions are broadly flat and are now the biggest contributor (27%). There has also been precious little progress in residential or agricultural. That means that for the past thirty years, the UK has met its emissions targets with very little disruption to UK households.

In the coming decades that has to change. The CCC urges policymakers to look to buildings, transport, lifestyles and agriculture for further emission reductions. The French may nickname us Les Rosbifs, but the CCC warns our diets should contain 20% less beef, lamb and dairy to help reduce agricultural emissions.

Aviation too is problematic. Unlike car fuel, there are not yet viable alternatives to jet fuel, which must be able to combust in temperatures as low as –30°C. Yet measures to curb demand for flights will not be popular in a nation accustomed to an annual worship of Iberian sun.

Cleaning up after ourselves will inevitably come at a cost. The CCC estimates that the cost to the UK to achieve net-zero by 2050 is 1–2% of GDP annually. The Chancellor Philip Hammond has quantified this as being over £1 trillion. He argues that the CCC’s policies would demand public spending and borrowing, channelling funding away from other priorities like schools and hospitals. It might also mean higher energy and living costs for families.

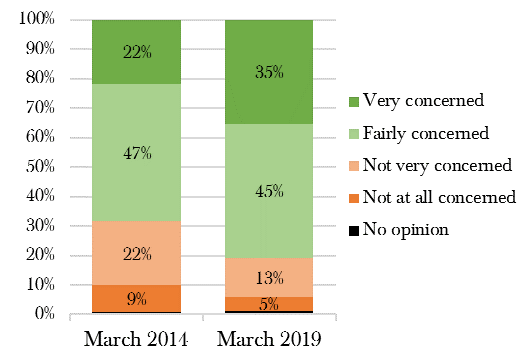

Hammond fails to mention, however, that it will be even more expensive to reach net-zero the longer we wait: removing greenhouse gases from the atmosphere once released is extremely costly. He further fails to acknowledge the benefits of less pollution and new green industries and jobs, or the increasing levels of public concern about climate change (Chart 3).

Chart 3: Public concerns about climate change in the UK

(Source: BEIS Public Attitudes Tracker, March 2019)

If we therefore conclude that change is coming, what does change look like? 75GW of offshore wind, up from 8GW today. The electrification of transport and heating, resulting in a doubling of electricity demand. A transition away from gas boilers for 29 million existing homes. Better insulation, windows and draught proofing. Installing 1,200 rapid chargers near major roads, and a further 27,000 in towns across the country. Mass afforestation in the UK with the planting of 30,000 hectares of trees every year. The development of a carbon sequestration industry.

It should be unsurprising that decarbonization is a major theme for a number of the funds in our Sustainable World services. As we have discussed, the opportunities are vast. The Liontrust Sustainable Future range of funds, for example, invest across three broad themes and twenty sub-themes including improving the efficiency of energy use and making transportation more efficient. Holdings include Kingspan, the Irish manufacturer of insulated panels and other energy-efficient building materials, and Hella, a German manufacturer of auto components including auto-dimming energy-efficient LED headlights. Royal London Sustainable Leaders Trust holds Infineon, a German manufacturer of semiconductors used in the automotive industry, power management, industrial power control and digital security. High quality semiconductors help with efficient energy transmission and storage (with applications in renewable energy), help to build more autonomous and cleaner transport systems, and reduce the energy consumed by electronic devices.

Elsewhere, John Laing Environmental Assets owns and operates a portfolio of environmental infrastructure assets across wind, solar, waste and wastewater, and anaerobic digestion. Such is the growing opportunity set that this trust has recently raised equity several times, funding further acquisitions of anaerobic digestion assets, which effectively turn feedstock into a bio-gas which is ultimately fed into the national grid. We are currently conducting due diligence on this trust’s close peer The Renewables Infrastructure Group, which is a much larger investment trust with a greater focus on onshore wind assets (currently 80% of its portfolio), growing exposure beyond the UK and Ireland (currently in Sweden and France) and a contracted link with a day-to-day operations management company. SDCL Energy Efficiency Income Trust owns energy-efficient power generation assets, including combined heat and power engines and rooftop solar arrays, plus assets which use power more efficiently, such as LED lighting systems. These assets provide their users with cleaner, cheaper and more reliable energy.

Ian Woolley CFA – Senior Investment Analyst

Ian Woolley CFA – Senior Investment Analyst

This document is issued by Hawksmoor Investment Management Limited (“Hawksmoor”) whose registered office is at 2nd Floor Stratus House, Emperor Way, Exeter Business Park, Exeter, Devon EX1 3QS. Company No. 6307442. This document does not constitute an offer or invitation to any person in respect of any investments described, nor should its content be interpreted as investment or tax advice for which, if you are an individual, you should consult your independent financial adviser and or accountant. The information and opinions it contains have been compiled or arrived at from sources believed to be reliable at the time and are given in good faith, but no representation is made as to their accuracy, completeness or correctness. Hawksmoor, its directors, officers, employees and their associates may have a holding in any investments described. Any opinion expressed in this document, whether in general or both on the performance of individual securities and in a wider economic context, represents the views of Hawksmoor at the time of preparation. They are subject to change. Past performance is not a guide to future performance. The value of an investment and any income from it can fall as well as rise as a result of market and currency fluctuations. You may not get back the amount you originally invested. With regard to any of the Hawksmoor’s managed Funds, please read the prospectus and Key Investor Information Document (“KIID”) before making an investment.