Because something is happening here

But you don’t know what it is, do you, Mister Jones?

– Bob Dylan, Ballad Of A Thin Man, 1965

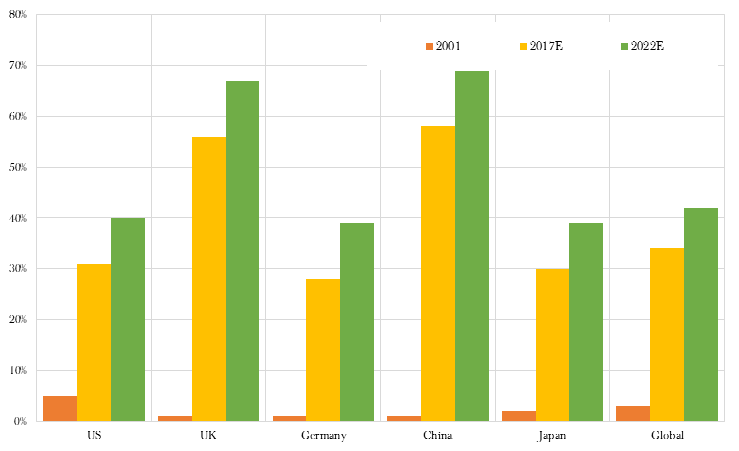

Advertisers spend an aggregate $550 billion annually in a bid for a few moments of our rare attention. The narrative in recent decades tracked the rapid shift in output media from traditional to digital (Chart 1), the corollaries for newspapers and television, and the birth of media titans Google and Facebook. Agencies, advising the advertisers, skipped from the old world to the new not only unscathed but also more profitable than ever.

Chart 1: Digital as a % of Total Ad Spend

Source: GroupM

That, however, is beginning to change. Now advertisers are asking difficult questions about both the effectiveness of new media and whether their longstanding trust in their agency advisers has been woefully misplaced.

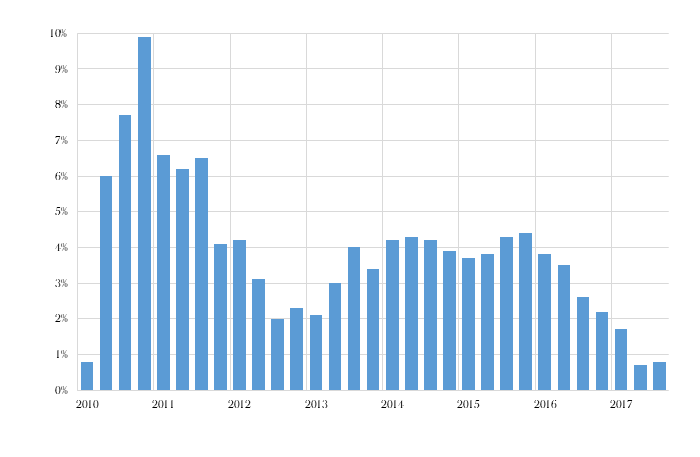

For the big ad agencies, 2017 has been a painful year (Chart 2). WPP has downgraded its expectations for the year thrice; its share price has fallen over 30%. Similar fates have darkened doorsteps at Publicis, Omnicom and Interpublic: shares are down by an average 20% year-to-date (Source: FactSet). In this report, we consider this changing market and assess the nature and extent of the threat to the agencies.

Chart 2: Ad Agency Aggregate Organic Growth (%)

Source: IPG, OMC, WPP, PUB, HAV

The Great Rip Off

Media buying used to be simple: so many square inches in a newspaper, or so many seconds in the Coronation Street ad break. The chain from advertiser through media buyer to publisher was short and relatively transparent.

In the age of programmatic digital advertising, it is more complicated. Added to the food chain are tracking and third party verification services, demand- and supply- side platforms, ad servers and data exchanges. Then there are the thorny issues of when a click is a click and a view is a view: last year Facebook admitted it had grossly overstated the average time users spent watching advertisers’ videos. The water muddies further when brands’ adverts appear beside objectionable content, such as the new Mercedes A-class next to a YouTube video endorsing Islamic extremism.

The accusation is that not only are advertisers receiving poor value for money, but also that amidst this opaqueness ad agencies have been ripping off their clients. Procter & Gamble (P&G) cut $100m from their second quarter digital marketing spend and claimed there was no impact on growth. In other words, some of the ways agencies made money in the past decade appear to be mostly superfluous.

Cost cutting to success

With uncertainty over the value of digital marketing, added to pressure from activist investors to improve profitability, corporates have feverishly axed their marketing budgets. Kraft’s audacious £115bn bid for Unilever, though refuted, scared Unilever’s management into drastic cost cutting to expand near-term margins. Hyperactive cost cutting has also been prevalent at Ford, Nestlé and Reckitt Benckiser.

These brands risk throwing the baby out with the bathwater. Benefits accrued from cost cutting can only go so far; thereafter such downsizing can affect both growth and profitability. Often, however, the damage to market positions and brand strength is not immediately obvious.

The wider context for consumer goods brands is intense competition from the discount sector. Supermarkets, in a bid to both lower prices and protect their margins, have prioritised own-brand sales. Consider, for example, the success of Tesco’s farm-branded value range compared to the penurious blue-and-white Tesco Value of yesteryear. Sainsbury’s now expects of its suppliers that its own shampoo is at least as good as the branded equivalent.

Consumers, in turn, are showing a willingness to forgo the brand name in the interests of value. Increasingly, that a food product is sourced locally and humanely matters as much as the name on the packaging. In this environment, the big brands cannot afford not to differentiate their offering through innovation and marketing. Our supposition is that the slowdown in marketing spend by the major brands will prove to be temporary: successful businesses must invest in their brands and engage with their audience.

Shifting competitive sands

The nature of the competitive environment in which the agencies operate is changing, though we do not agree with concerns that this poses an existential threat.

Newcomers to the party include management consultancies, such as Accenture and Deloitte, that have muscled in on the promise that they can independently audit marketing efforts. Given the opaqueness on digital media pricing and output that we noted earlier, Accenture finds receptive CEO ears. In value terms, however, the impact is minuscule. The consultancies – at least for the time being – lack the scale to pose a serious threat to the incumbent agencies.

Similarly, in the climate of distrust, certain media contracts have been brought back in-house to avoid alleged conflicts of interest. Again, however, the impact is still marginal.

The more material competitive threat comes from the normal functioning of the market. Brands are reviewing their media spending, and a panicked (and probably oversupplied) industry is offering uneconomic deals to retain or win work at any cost. Earlier this year, Sir Sorrell, CEO of WPP, quipped in response “our industry may be in danger of losing the plot”. This means near-term downward pressure on fees and margins, though we would expect this threat to be cyclical, rather than structural, in nature.

Disintermediation: the birth of giants

A further anxiety is that advertisers can now transact directly with publishers (by utilising Google Adwords or Facebook Business): is the role of media buyer obsolete? That Google and Facebook combined account for 60% of digital media sales means they are an enormous disruptive threat.

We believe the existential threat to the ad agencies from disintermediation is limited. The risk that Google becomes a direct competitor to WPP et al. is low, not least because advertisers want some independence from publishers when taking budget advice. There is still a role for the ad agencies in the creative process, marketing strategy and media buying. As technology evolves, brands will increasingly come to rely on consultative external expertise.

This thesis is supported by data: WPP’s digital media share has been relatively consistent over recent years at just under 20%. In other words, there is no noticeable disintermediation effect in current trading. Indeed, the growth of direct-to-publisher cometh chiefly from the long tail of smaller firms where the agencies generate little of their business.

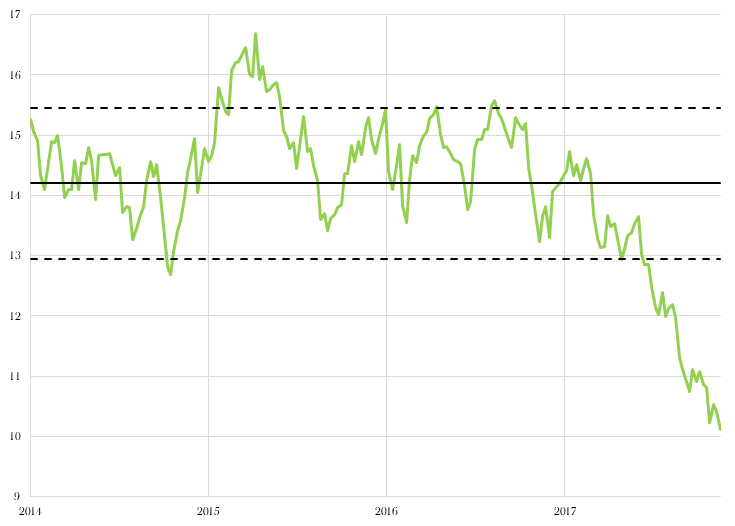

Valuation

The market reaction to the slowing of organic sales rates, and the worries that has fostered, has been severe. Chart 3 below shows the sharp de-rating of London-listed WPP plc this year from a premium valuation to just 10x earnings. At the time of writing the dividend yield is approaching 5% – a level that has not been seen since the market crash of 2008 (Source: FactSet). Though the market’s disfavour may persist for some time, we believe the current share price deeply undervalues WPP’s prospects.

Chart 3: WPP price-to-earnings ratio (forecast), 2014-2017

Source: FactSet

Conclusion: creative value

Ultimately, questions on the future viability of the agencies address their economic value-creating role. At their core, the agencies are networks of entrepreneurial individuals that seek to offer best-practice expertise on a wide range of marketing specialisms and scale, where it matters, in media buying. For the creative process, marketing strategy, planning and media buying, we would argue there is still an important role for the agencies to play.

As the industry develops and new ways of communicating with consumers evolve, agencies certainly need to adapt. Our thesis is that this change is possible and that the fears over new competitors, transparency and disintermediation have largely been exaggerated.

Ian Woolley – Senior Investment Analyst

Health Warning/ Disclaimer

This document should not be interpreted as investment advice for which you should consult your independent financial adviser. The information and opinions it contains have been compiled or arrived at from sources believed to be reliable at the time and are given in good faith, but no representation is made as to their accuracy, completeness or correctness. Any opinion expressed, whether in general or both on the performance of individual securities and in a wider economic context, represents the views of Hawksmoor

at the time of preparation. They are subject to change. Past performance is not a guide to future performance. Hawksmoor Investment Management Limited (“Hawksmoor”) is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority. Hawksmoor Investment Management Limited is registered in England No. 6307442 and its registered office is at 2nd Floor, Stratus House, Emperors Way, Exeter Business Park, Exeter EX1 3QS.

FOR PROFESSIONAL ADVISERS ONLY AND SHOULD NOT BE RELIED UPON BY RETAIL INVESTORS