Trillion Dollar Babes

The long hot summer has passed into autumn. The long hot bull market is showing unmistakable signs of fatigue. The markets though are not mirrors of the seasons and weariness need not necessarily be followed by financial winter. But like the dormouse, the hedgehog and the grizzly bear, a good sleep may be in order.

US equities are ploughing a lone furrow

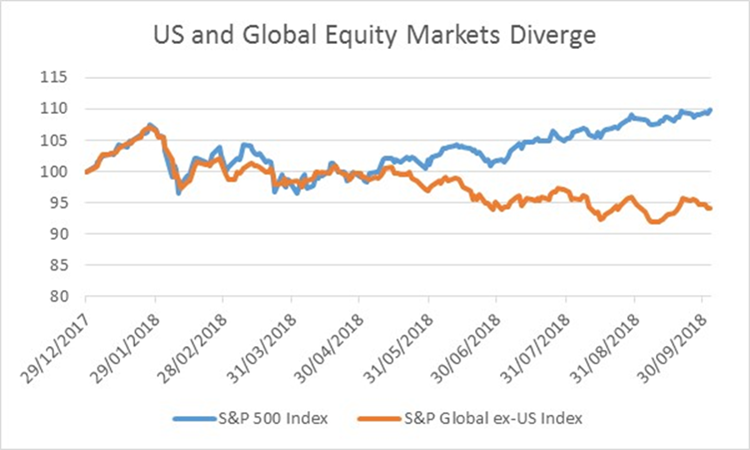

It would be an exaggeration to say that markets in the third quarter of the year became a one trick pony, but it is not far off the truth. Broadly, US equities are ploughing a lone furrow and everywhere else has started to struggle. This is not something that is going to last forever, perhaps not even to Christmas. The question now is which is going to prevail: American optimism or global realism?

It is not our role to either defend or lambast Donald Trump. Our perspective is mostly delivered by the British media and we have no doubt views of the American president change when one crosses the Atlantic. What is undeniable is that he is in office while US economic data and corporate profits are reported to be improving, possibly quite sharply. He is also the president who saw the creation of the first trillion dollar company. That is quite something to have in one’s obituary.

Few can have failed to have seen that in early August, Apple became the first company to have its equity valued at more than a trillion dollars. If only for the sake of showing how spectacular a dozen zeros look on paper, that is $1,000,000,000,000. It was only another five weeks until Amazon doubled the membership of the Trillion Dollar Babes Club. There is a resonance of history here. Apple first listed its shares in 1980, which was the year in which the total value of companies on the New York Stock Exchange reached $1 trillion.

But there is a problem with the Apple story: it is, quite simply, wrong. Apple is not the first member of the Trillion Dollar Babes Club. The title actually belongs to PetroChina, back in 2007. Apparently though Chinese businesses do not count, especially when it is inconvenient to an otherwise great American success story. The laudation accorded to Apple on being the first Trillion Dollar Babe is what might be called ‘fake news’, or even propaganda.

As a quick aside, there is thick fog surrounding the first company to be worth a billion dollars. This is widely accepted to be United States Steel Corporation, back in the mists of 1901. Again, this is not strictly true as around a third of the value was a mortgage bond and not equity. The title probably belongs to Standard Oil some fifteen years later, although even this is subject to considerable interpretation. We should also make mention of inflation: allowing for this adjustment, the value given to the Dutch East India Company in the 1790s would now be worth almost $8 trillion. That probably makes it the most valuable company of all time.

Away from America, equity markets have found the summer rather more of a struggle, as the chart below shows. The combination of rising US interest rates, a strong dollar, Brexit and the threat of trade wars has hung heavy. Developed markets have been treading water, whereas emerging markets have borne the brunt of investors’ nerves. This has been quite unhelpful for many of our portfolios, which typically have relatively high exposure to Asian and other emerging markets.

Chart US and Global Equity Markets Diverge

Source: FactSet, S&P Dow Jones Indices

There is logic to the victimization of emerging markets, though we are confident that the phase will pass. It is a feature of many developing countries that governments borrow in both their own currencies and in US dollars. When the value of the dollar rises, so does the cost of paying interest on these debts. In extreme cases this can result in the country running out of dollars and then having to print more and more of its own currency; devaluation, default and a visit from the IMF follow shortly thereafter. Step forwards Argentina.

The good news is that we do not believe these issues are endemic. Emerging markets are typically less indebted than many developed countries and are frequently growing their economies considerably faster. The market’s phase of scaremongering will pass. This is not to say that there will not be further mishaps and we remain especially wary of the situation in Turkey, where the country is crucial to America’s attempts to reshape the political and geographic maps of the Middle East.

As much as we might wish to, we cannot avoid discussing either Brexit or the so-called trade wars. The former is undoubtedly depressing asset prices in both the UK and, to a lesser extent, Europe. It is to the credit of neither side that less than six months from the day that the UK leaves the European Union the process of so doing appears to be so shambolic. The Conservative Party is in disarray, leaving open not only all possible Brexit outcomes but also the spectre of a Corbyn-led far left Labour government. It is hardly surprising that so many global investors view the UK as a risk too far.

Brexit is a situation in which the investment penalties for being wrong substantially outweigh the rewards for being right. We believe it is dangerous to bet outright on any particular outcome and we are therefore keeping a deliberate balance in asset allocation and stock selection.

This balance though comes with a skew: the downside risk to UK assets (equities, gilts and the pound) of No Deal is in our view greater than the potential rise should compromises be reached. On the other side of the scales, domestic stocks come at a substantial discount to those with greater international earnings.

We also fear that any possible Brexit outcome will be so unacceptable to enough of the Conservative Party that none would be supported by sufficient to pass through Parliament. It is hard to escape the feeling that, to many Conservatives, opening the door to Jeremy Corbyn is preferable to supporting a Brexit deal with which they disagree. Whilst it is very hard to maintain a rational investment stance in the midst of such a mess, we thus have a deliberate anti-sterling and pro-overseas-earnings tilt in our portfolios. We stress that we keep feet in both camps and our tilt is not to the exclusion of the unloved, and much cheaper, domestic stocks.

Is Brexit opening the door for Jeremy Corbyn?

We have consistently argued that the United States would not seriously antagonize China over terms of trade. The former is, in our view, too dependent on the latter to keep buying the treasury bills that it has to issue to fund the government deficit. We confess that our nerves are being tested, with both sides showing considerable brinkmanship skills. Compromise is still much the most likely outcome, whilst allowing Mr Trump to tweet that he has won a war. If this is the only war he fights during his presidency, perhaps we should all breathe a sigh of relief.

We come finally to American interest rates. Perhaps the single most important determinant of the course of financial markets over the next six months is the aggression, or restraint, with which the Federal Reserve tackles the perceived problem of labour shortages in the United States. The Fed is walking a fine line between risking inflation and creating recession. Markets believe Jay Powell, the new Chair, has mastered the tightrope. The question is how long he keeps doing so.

Jim Wood-Smith – Chief Investment Officer, Private Clients

Jim Wood-Smith – Chief Investment Officer, Private Clients

What’s Your Brexit?

Brexit is almost upon us. Going back to the pre-referendum campaigns, the UK’s withdrawal from the European Union has been, at best, poorly explained. At worst, it has been deliberately obfuscated. Here we set out and try to explain what we see as the four core possibilities, together with their likely impact on financial markets.

No Deal

This can effectively be doubled up as a ‘Hard Brexit’. The UK immediately leaves all agreements with the EU, without a transition period. Trade tariffs revert to World Trade Organization terms (i.e. higher). The impact on Services is not yet explained, but it is expected that financial institutions will lose all passporting rights and therefore will be unable to do business in the EU until they have obtained new regulatory approvals. Short-term disruption to trade may be significant; BMW for example has brought forward its summer shutdown to coincide with Brexit to mitigate the risk of supply disruption. Expats may lose access to annuity-based pensions. Professional qualifications will likely not cross borders. Organic farmers will need to re-seek certification in order to export. There will be a hard Irish border. The UK will be free to negotiate new non-EU trade agreements. The UK will not be subject to the European Court of Justice.

Market Impact: in the short-term, this is the scenario that the markets fear most. The economic impact in 2019 would be severe, what would happen thereafter though is subject to complete conjecture. UK assets – equities, bonds and the pound – will fall. Some sanctuary could be found in overseas earners.

Chequers Plan

A Soft Brexit. The Chequers Plan broadly allows both sides to make everything up as they go along. The Plan’s major shortcoming is that on trade it covers goods but not services. Thus the fate of 80% of the UK economy is yet to be postulated. Chequers proposes a ‘common rule book’, facilitating continued harmonization with European rules. But not in all cases, as the UK’s Parliament will still have the right to diverge if it sees fit. The UK would be free to set its own tariffs with the rest of the world. The same compromise applies to the courts, where there will be a ‘joint institutional framework’ with British courts paying due regard to EU case law. Free movement of labour will end, but in practice would likely continue. The Irish border would remain open.

Market Impact: mild negative. There is too much in the Chequers deal subject to ‘make it up as we go along’ to provide the certainty to markets that the UK is again a safe place to invest.

Norway

Possibly the Softest Brexit. This proposal is that the UK should (re)join the European Free Trade Association (EFTA). The current EFTA members are Norway, Iceland, Lichtenstein and Switzerland. The implication is that the UK would then adopt EFTA’s trade arrangements with the EU. EFTA members are free to negotiate their own non-EU bilateral trade agreements. The complication with this potential solution is whether the UK should choose to remain part of the European Economic Area (EEA); membership of this is available only by being part of either the EU or EFTA. At present, Switzerland opts out. The EEA applies around 45% of EU rules to all members, hence the argument that going down this route would allow the UK access to the EU markets, but without a say on how the rules are made. The customs union applies only to the EU and not the EEA, so the UK would leave this and could decide to remain in or renegotiate agreements such as the Common Agricultural Policy and Common Fisheries Policy. The legal aspects of the UK’s relationship with the EU would be handled by the EFTA courts. The Irish border would remain open, as would freedom of movement with all of the EEA.

Market Impact: mild positive. This is the type of deal that the markets wish to happen. It comes with a largely established framework of rules, providing a good degree of certainty. Equity markets and the pound would probably rise.

There is too much in the Chequers deal subject to ‘make it up as we go along’ to provide the certainty to markets that the UK is again a safe place to invest.

Canada

Baby Bear’s Bed. This is a bespoke free-trade arrangement. Canada has tariff-free trade with the EU, but has more regulatory hurdles to clear to achieve this. It also has more restrictions on the supply of services. Notably Canadian financial services do not have access to the European market. The deal took seven years of negotiation to complete; it is not explained what will happen in the interim while the two sides horse-trade. The issue of the Irish border is unresolved.

Market Impact: likely to be negative in the short-term, dependent upon the speed of negotiations. If both sides could convince markets that a bespoke free-trade arrangement can be agreed quickly, then market falls should be modest.

Ian Woolley CFA – Senior Investment Analyst

Ian Woolley CFA – Senior Investment Analyst

Bonds and Equities – a Generational Mismatch

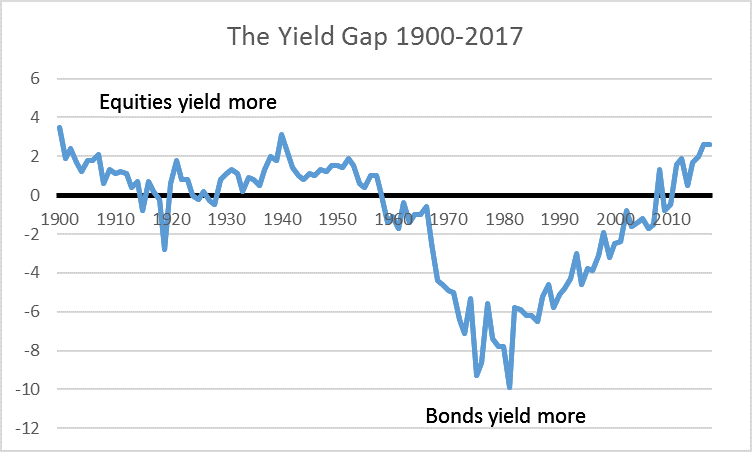

It is frequently said that equity investors should be wary of rising bond yields. The argument is that the better the available returns from bonds, the less attractive equities become. Indeed, some of the more apocalyptic commentators have said that as and when markets turn, the values of both equities and bonds are set to plunge. You may be glad to read that we disagree. Not only that, we have nearly 120 years’ worth of data to show why.

The history of the relationship between equities and bonds can be simplified into three periods. These are: the world pre the 1950s, the 1950s to the Great Financial Crisis, and 2009 onwards. In the first of these, it was accepted wisdom that equities should pay a higher yield than gilts because they were riskier. Companies’ fortunes ebbed and flowed, and dividends were cut in bad times. To compensate for that risk, investors demanded a higher dividend yield than that of perceived safe assets. The difference in the levels of income was named the “yield gap”.

Chart The Yield Gap 1900-2017

This “yield gap” held true as a rule of thumb until the 1950s. That was the decade when George Ross Goobey, a young-ish Bristolian fund manager at the Imperial Tobacco Pension Fund, persuaded the trustees of the fund that the logic no longer held true. This was revolutionary. Equities, he argued, were the only means of protecting the worth of the pension fund against inflation, which lowers the real value of bonds but allows companies to increase their dividends. The conclusion was that, in the presence of inflation, bonds should yield more than equities to compensate for the new risk of real depreciation. With a predictable lack of imagination, the presence of the higher bond yield was dubbed the “reverse yield gap”.

The newly accepted wisdom held good, with one or two exceptions, until the Great Financial Crisis. Indeed, it was one of the stark explanations for the Black Monday crash of 1987. Analysts studied the history of the relationship between the yields on equities and gilts and spotted that the difference had become extreme. Prior to the 1987 crash, gilts yielded an astonishing 2.4 times more than equities. A swift 25% fall in equities soon brought that back to a more sensible level.

The post Great Financial Crisis era has been defined by the financial policy known as Quantitative Easing. This is a process in which central banks buy bonds, both to create liquidity and to reduce bond yields. It has been a period in which the relationship between the returns from equities and gilts has decoupled from history. As we previously mentioned, in round numbers the UK equity market dividend yield forecast for next year is close to 4%. The yield on the gilt maturing in ten years’ time is roughly 1.5%. That is an unprecedented change in valuation, one that implies prolonged deflation and very low rates of economic growth. We see neither. Were we to apply the same 1987 valuation to current markets, this gives us a gilt yield of closer to 10%. That is an extreme example, but gilt yields can treble before they ought to threaten equity valuations. That is a long way to go.

When we argue that history suggests we need not be worried about rising gilt yields, there is very strong evidence to support this. Moreover, history implies that quantitative easing has resulted in equities being generationally cheap relative to bonds. The trouble is that it may take a generation for normal service to be resumed.

James Clark – Senior Fund Analyst

James Clark – Senior Fund Analyst

This document is issued by Hawksmoor Investment Management Limited (“Hawksmoor”) whose registered office is at 2nd Floor Stratus House, Emperor Way, Exeter Business Park, Exeter, Devon EX1 3QS. Company No. 6307442. This document does not constitute an offer or invitation to any person in respect of any investments described, nor should its content be interpreted as investment or tax advice for which, if you are an individual, you should consult your independent financial adviser and or accountant. The information and opinions it contains have been compiled or arrived at from sources believed to be reliable at the time and are given in good faith, but no representation is made as to their accuracy, completeness or correctness. Hawksmoor, its directors, officers, employees and their associates may have a holding in any investments described. Any opinion expressed in this document, whether in general or both on the performance of individual securities and in a wider economic context, represents the views of Hawksmoor at the time of preparation. They are subject to change. Past performance is not a guide to future performance. The value of an investment and any income from it can fall as well as rise as a result of market and currency fluctuations. You may not get back the amount you originally invested. With regard to any of the Hawksmoor’s managed Funds, please read the prospectus and Key Investor Information Document (“KIID”) before making an investment.