We are all back in the office this week. After the best part of three weeks out on the road extolling the virtues of Hawksmoor, it is back to reality today. ‘Reality’, of course, is a euphemism for complaining about the air conditioning and wondering how it is possible to receive quite so many utterly irrelevant emails.

But thank you to everyone who came to listen to us. The plan is that our roadshows are genuinely worth your time and that we can give you something different to any of our peers. If we fall short on either, please do give us an encouraging smack on the wrist.

One of the alleged benefits of technology on one’s working life is the ability to look at stuff when away from the office. Most of the time, that would be a bad thing, but it does mean that one can spend that much time away without losing one’s handle on wot’s occurring.

Company results come in a torrent at this time of year. You will have seen, I am sure, that Amazon has reported that it is doing jolly well and that its equity market value is again just nudging on a trillion dollars. You may, though, have missed that the oil companies around the world are faring considerably worse.

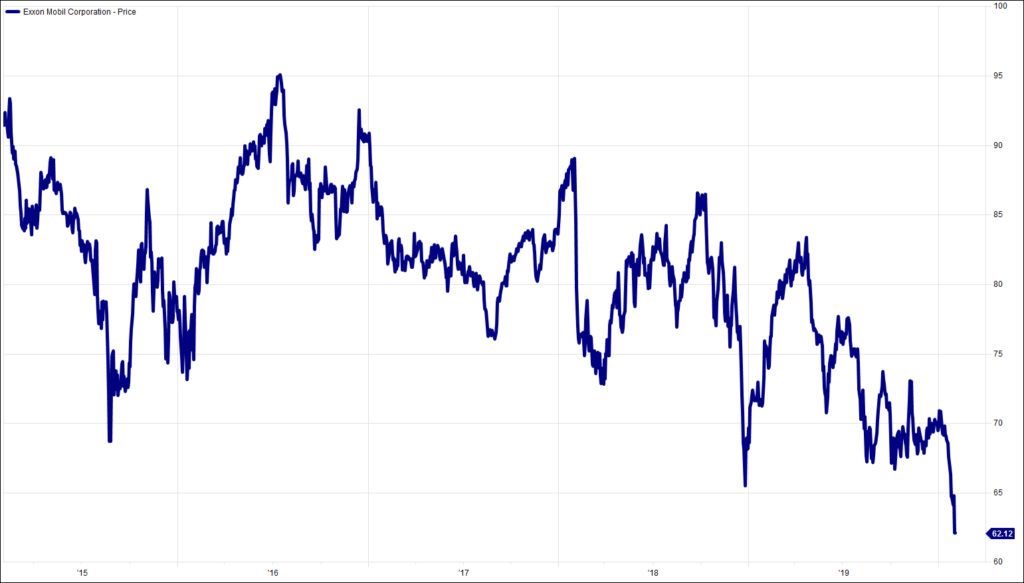

I am indebted to Bloomberg for including some sectoral data on the US Energy Sector in its report on the woes of Exxon and Chevron. The sector currently accounts for a mere 3.8% of the equity market, having peaked at 16% in 2008. Its weight has halved in the past five years alone. That is quite something.

This, though, is not another diatribe about how this is the end of the oil era. Or even about how undervalued oil stocks are in the new world of sustainability (discuss). Au contraire. It is compare and contrast the US and UK.

So, in these past five years in which the weight of the US energy sector has halved, what do you suppose has happened to the weight of the UK sector? Let me put an end to your head-scratching. It has barely moved.

This teaches us volumes about the difference between the two stock markets, and indeed economies. The US has been home to the rise and rise (and rise) of technology. Here in the UK, what do we have to take the place of the declining hydrocarbon industry? Zilch is the simple answer. And herein lies the reason why the UK’s headline equity indices are broadly the same level as in 1999, whereas the S&P 500 Index has more than doubled.

To look at a list of the largest companies in the UK is to see a conglomeration of the mature, the low growth and the cyclical. The number of younger, dynamic, faster growing businesses is pitifully low. What one gets from the UK’s largest companies is income. If we look at the total return (with gross dividends reinvested), the return from the past 20 years rises from zero to 130%. That is quite a different perspective. This is not to say that we are devoid of fantastic businesses in the UK. They are there, just hidden in the reed beds of the lower regions of the market.

But how many great UK businesses can you name that have been founded in the last twenty or thirty years and are now global leaders? Where are our Amazons, our Googles, our Microsofts, our Facebooks, our Apples? Those are the five largest companies, by value, in the United States. Ours are Royal Dutch Shell, HSBC, AstraZeneca, BP and GlaxoSmithKline. British American Tobacco still comes in sixth, despite its share price having dropped 40% since mid-2017.

It is a statement of the blindingly obvious that Boris has more on his plate than Mr Creosote (with thanks to the sadly missed Terry Jones). But one might argue that amongst his greatest challenges is the need to create the environment in which new, younger, dynamic British businesses can genuinely thrive. He is giving very mixed messages on this front (on every front?). He has an opportunity never previously afforded to a prime minister (this is, as far as I am aware, the only time we have left the European Union). We all hope that he does not waste it.

The customary congratulations to everyone who knew last week’s reference to Michael Portillo. Today, why might yesterday have been described as ‘never odd or even’?

Chart of the Week:

Exxon Mobil, past 5 years

HA804/242

All charts and data sourced from FactSet

Jim Wood-Smith – CIO Private Clients & Head of Research

Hawksmoor Investment Management Limited is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority (www.fca.org.uk) with its registered office at 2nd Floor Stratus House, Emperor Way, Exeter Business Park, Exeter, Devon EX1 3QS. This document does not constitute an offer or invitation to any person in respect of the securities or funds described, nor should its content be interpreted as investment or tax advice for which you should consult your independent financial adviser and or accountant. The information and opinions it contains have been compiled or arrived at from sources believed to be reliable at the time and are given in good faith, but no representation is made as to their accuracy, completeness or correctness. The editorial content is the personal opinion of Jim Wood-Smith, CIO Private Clients and Head of Research. Other opinions expressed in this document, whether in general or both on the performance of individual securities and in a wider economic context, represent the views of Hawksmoor at the time of preparation and may be subject to change. Past performance is not a guide to future performance. The value of an investment and any income from it can fall as well as rise as a result of market and currency fluctuations. You may not get back the amount you originally invested. Currency exchange rates may affect the value of investments.